(Fotoğraf: Refik Akyüz)

We invite you to in our space Rosenthal, to share with you the pain that the attack on free speech and democracy is doing suffer to you and to your country. (http://web.tiscali.it/cepsidi/spaziorosenthal.htm)

This our first thought for you:

The scope of psychoanalysis is unlimited as it spans the entire territory of the unconscious, its mechanisms, its manifestations, its productions and structures. If one cannot affirm the analyst has a free access to these territories, certainly it can be said he or she has a privileged view onto them. Indeed, taking the move from the premise of the unconscious no distinctions of time, space, gender, race or ethnicity can be drawn to build walls and separate human beings. The other is always inside us and it needs to be given shelter, as we – the psychoanalysts – have learnt throughout hard challenges and the unceasing work carried out on ourselves.

In this sense we never entirely overlap with the institutions to which we belong. If we make an opening to the pain that we hear from the letters of the Turkish colleagues today, it is because they metaphorically give back to words their meaning, renewing the sense of one that always had a particular sense: freedom.

This special relevance of the word freedom comes from the traumatic background represented by the fact of being alive in a specific subjectivity, which is eventually part of a greater History. When we are faced with texts like those by Janine Alounian, where surviving becomes not only a dramatic testimony of the genocide of an entire people, the Armenian, but also a great metaphor of the survival of what she considers as something precious, psychoanalysis itself. Therefore we are called but to feel at the frontline of the struggle for freedom when the Turkish police beat a psychoanalytic working group on homosexuality in the premises of the university.

We express this solidarity in this space, as best as we can, considering also the urge to share now our participation to the trauma we indirectly suffer, together with our female colleagues who experience it directly suffer indirectly, but with no lesser intensity for the afore-mentioned reasons.

As evoked by Hannah Arendt, after attending the Eichmann trial, evil with all its banality reappears with its chilling presence in our everyday life, and it continues to amaze us despite the harsh experience of living in contact with history.

Laura Montani

Full member SPI

CPdR

Roma

curator of Space Rosenthal

Dear Laura,

In these tough days in which we have been breathing in tear inducing gas from bombs, I would like to say that your letter has had as refreshing an effect as the cool breeze of the Bosphorus. So is your invitation for us to work on what is happening psychoanalytically and to express them on your website and your promise that these non symbolized raw experiences can transform, can be transformed through word, writing, thinking and co-thinking. I thank you for your generous invitation on my own behalf.

Despite needing an afterwardness (apres-coup) experience in order to analyze some phenomena, especially ones that are traumatic, so as to ponder upon and understand them, psychoanalysis gives us the tools to think – in depth – also in the moments that the events are being experienced or at least shows us the way into finding which tools we can use. In this letter that serves as a reply, I will try to write about my thoughts on the Gezi incidents as a psychoanalyst, with reference to Janine Altounian and Hannah Arendt of the writers you have recommended.

I suppose you have followed from the media, the pioneer of the Gezi movement is an urban, educated youth of ages from 18 to 30. Women make up a little more than 50% of the participants and in addition to being the majority are more visible in comparison. Efforts made in order to take the movement under the patronage of some political parties have failed and the youth has bravely displayed their own dynamics and demands in their own words, with their own unique and aesthetical style, with creativity and wit. Social media has surpassed the silent press and audiovisual media and we were able to follow the incidents in all their nakedness in real time. These young people not only occupied the park but also fought back against the police and their disproportionate use of force. They proposed, in their own words, “disproportionate intelligence” against disproportionate force. They continued to carry on with their resistance peacefully through actions of civil disobedience and not only amazed their parents who were sitting on the edges of their seats but also transformed them. Mothers actively participated in the resistance holding bills that read “I am proud of my child” as a response to the prime minister and governor’s call for parents to retract their children from the park a few days prior to the defusing of Gezi Park with police intervention. Who were these women? Who were these parents that supported their children and eventually helped this movement to evolve into a loud and clear expression of “enough is enough – ras le bol!”?

These parents were of the generation that first handedly experienced the trauma of the 1980 military coup and could not sufficiently symbolized, subjectified, appropriatively subjectified the malign repercussions of this coup. This fraction of people who were high school or college students in the beginning of the 70s when the demands for freedom and opening up to the west had just started to stir had been exposed to the coup and its destructive aftermath in their most valuable years. Although the political activities of students from both the left and right wing were oppressed with violence, torture and deterrence policies, recent research has shown that the left wing has been left more wounded. This fraction of people who are now above 45-50 years old had only experienced freedom as a concept in philosophical texts and had only timidly come closer to it in literature and art. Freedom was an outlook, a dream but, most importantly, was not a concept concerning public life. We could not make it function by taking it to the “city”. This coup had not only strengthened the traditionally authoritative and prohibitive mindset that was already present in the culture, but also left a lasting scar on education, science and the culture itself. It was this scarred youth of the parents and thenon symbolizied remains of the coup that the young people of Gezi set to work on. These young people expressed matters that their parents could not even dare to think about and also stood up to the state. With this opposition, everything in Turkey that could not be discussed sufficiently was brought out to the open. The youth’s brave attempt broke the silence and also injected libido to all of the bitter and hopeless fractions. Gezi Park brought together different civil society organizations in a matter of a few days. For example, a young militant from Kurdish movement walked hand in hand with a Kemalist militant. Those that live in the select neighborhoods of Istanbul gained awareness about the state terror in the east. The unlawfulness of the construction that was to be made in Gezi Park lead to the expression of all of the unlawful happenings in the country; thanks to this movement we learned that Gezi Park was an Armenian cemetery that was impounded by the state. In a sense, this creative process in which the truths are expressed displayed the desire for the re-establishment of the paternal function of the state that had been interrupted due to state terror. Although young people have jokingly made the observation “Tayyip, connecting people”, I believe that what brought people together was commonly hanging on to the possibility that there could be a more just, free and new Turkey. Therefore, the tagline I propose is “Hope, connecting people”.

It is just here that I would like to refer to Winnicott’s concept of illusion. Because all of what happened caused most of us, especially those of us in the age range of the aforementioned parents, to think “Is this real, or are we imagining this?” The parents, although worried and wary, were on the youth’s side, which were tenacious in their belief in or desire/hope for a new Turkey. Winnicott speaks of a kind of magic in the happy meeting of the baby and the breast, that is, the breast being presented to him just at the time when he is hungry. Winnicott says that due to the fact that his needs are met at the exact time he needed them to be, the baby comes to the conclusion that his omnipotence has created the breast. This illusion makes up the basis of his belief that comes up later in life that he has the ability to create something, that is, the phenomenon that makes him feel that he is a subject, that he is the one doing something when he is; in short, owning up to his doings and becoming a subject. Another way to put it, being a subject requires omnipotence, since omnipotence challenges the boundaries of what we can do and invites us to a potential space which is the cradle of creativity, which is beyond those boundaries and is made up of both reality and imagination. What Gezi has triggered is the birth of a potential space that can facilitate this subjectivity and it is the expression of a collective desire for the establishment of transitionality processes that will create the circumstances of a more democratic country. Could we speak of the subjectivization of a society here?

And Turkey speaks, it speaks without getting involved in violence. Everyone has the right to have a say in the forums being set up in the parks of different neighborhoods. Just like how hysterics who could not speak but could express their desires with their bodies came to express and symbolize their pain with the help of Freud and Breuer’s hypnosis, cathartic method and lastly the free association method of psychoanalysis, the Turkish are also speaking. The Turkish are speaking of not only today but also of the past, are making room for witnesses, speaking more and more and we learn something new every day; not just about today but also about our past. Social media is bursting with all kinds of oral, visual and written documents. A caricaturist says: “You become so beautiful when you are angry, Turkey!” We talk about and archive these, and most importantly we talk to each other. We go beyond what the official history has made us memorize and a new image of Turkey appears before us. We see both our differences and our diversity and richness in this image. We see that our history goes back even before 1923, that our past is not solely made up of heroic epics and victories. That way, we are face to face with a new and different perspective of the past that is more realistic, more mature and involves less idealization. This perspective sets topics such as genocide, deportation, emptying and bombing of villages, the unlimited authority of the police and sadism on the table (on the couch?). What is best is that the admiration of the West and as a subpart of it, the idealization of the West has become relative in the fraction come to be known as the “secularists”. Young people who think as such say “The West can be a reference point, may provide an alternative way but Turkey cannot be a country in which ideas and methods are directly imported and marketed without any customization, interiorization.” What the Gezi youth has presented us all with is this demand to become a subject in our own history and the initiative to take the necessary and realistic steps for it. All cases of becoming a subject arise from the subject owning up to his life experiences and his history. In the words of René Roussillon, this appropriative subjectivity (subjectivité appropriative) is a must to becoming a subject. We should not forget to salute Freud here, when we observe that just like an individual would, the whole society who owns up to their identity follow similar psychic mechanisms. Freud has argued “In the individual’s mental life someone else is invariably involved, as a model, as an object, as a helper, as an opponent, and so from the very first Individual Psychology is at the same time Social Psychology as well—in this extended but entirely justifiable sense of the words.” The fact that the concept of subjectivity is a tool for being able to think about both individual and societal matters is due to groups and even large groups having, as group psychoanalysts such as Didier Anzieu and René Kaes point out, a psychic life just like individuals do. It is not a coincidence that this psyche is being called “the Gezi spirit”.

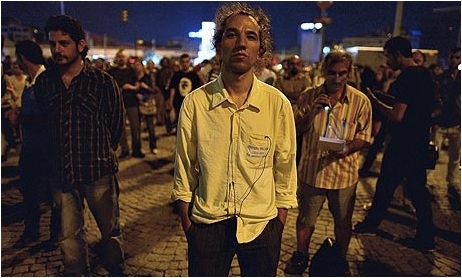

The other fraction that the Gezi movement has injected with libido is made up of social scientist, sociologists, psychologists and psychiatrist, who think and write about this movement, just like I am doing right now. We have been reading a wide variety of analyses. Some have interpreted this movement as a rebellion against the Father in the Oedipus complex, moving from the fact that the movement is an uprising. Some have emphasized the narcissistic and arrogant features of the leader. In this sense, some articles that can be described as psychobiography were published. Because the historical dimensions of this type of analyses have been widespread, I believe that the analysis they suggest remains unrooted. If the matter is about killing the father, we have witnessed many murders of the father in the Turkish history; the most important one being the dissolution of the army, the most primeval father, by the current government as well as the limiting of their power. But now maybe one can speak of another type of father-son relationship. One can talk about the son facing his father on his own, even though a societal support exists in the background. We should not forget the majority of the youth were uncomfortable with attempts by a political organization to lay claims to the movement; they did not want a new “father”. So now, there are benefits to be gained by looking at civil disobedience that was started by a performance artist and quickly spread around the world. ”The standing man” stands motionless in any part of the city. He does not speak, eat or drink, he just stands, stands alone. Aren’t we witnessing the birth of a new subjectivity, a new modern individual that does not sever his ties with the society but owns his solitude and most importantly tackles violence in the representational level?

Is it not this new generation, new youth that provides a good example of survival strategy by making the psychic and societal process that was once frozen by the previous two generations for the sake of democratization functional again with their appropriative subjectivity? I think we can connect this societal and genealogical situation to the survival of psychoanalysis that you have emphasized by referring to Janine Altounian’s work on her father’s diary. Doesn’t the survival of psychoanalysis leave us face to face with the same problematic? Doesn’t the next generation maintain continuity and embrace new readings that are to be born by discussing again and again the non symbolizied, not sufficiently analyzed readings, discussions, and conflicts that it has inherited from the previous generation?

I will conclude my words with a more hopeful and optimistic work by Hannah Arendt than Banality of Evil that you have referred to. In The Human Condition, Arendt argues that nativity, which she describes as a central category in political thought, is the actual miracle that saves the earth, since ontologically speaking the roots of the ability to act lie in nativity; that is, the birth of new people to the world is expectant of a new start and new action. Only this experience can bring with it hope and belief, which are the two basic features of being in human relationships. In a sense, Arendt argues that every new baby born to the world opens the doors to a new world.

Has the Gezi youth not thus materialized “survival” by injecting libido to the frozen psychic and political life of previous generations and presented this world with a new world with their acts?

With my best wishes,

Bella Habip

Member of Psike Istanbul

Member of SPP (Société Psychanalytique de Paris)

The Standing Man Erdem Gündüz stands at Taksim. (Fotoğraf: Vassil Donev/EPA)